During a 2011 review of medical device quality data, the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) noticed a variety of widespread manufacturing risks that were impacting product quality. A few of these risks included:

- An industry focus on regulatory compliance as opposed to adopting best quality practices

- Lack of adoption of automation and digital technologies, with manufacturers choosing instead to continue running long-outdated versions of software

- Virtually no competitive market around medical device quality

After obtaining feedback from both FDA and industry stakeholders, the CDRH launched their Case for Quality. The initiative’s intention was to identify best manufacturing practices and help medical device manufacturers raise their manufacturing quality level by shifting their focus from being compliance oriented to what really mattered – improving product quality. Through effective collaboration with companies and stakeholders, the Case for Quality established manufacturing standards for the medical device industry, providing the industry with clear objectives to strive for.

One of the key findings of the FDA’s Case for Quality initiative was that the burden of Computer Systems Validation (CSV) was deterring technology investments and as a result, inhibiting quality best practice. The FDA’s regulation 21 CFR Part 11 in 1997 and the related guidance of 2003 created the clear foundation for implementation of Computer System Validation (CSV) processes. Adhering to FDA CSV guidance can be a challenge for life science organizations, however. CSV guidelines prioritize documentation, primarily to appease auditors, which can be both time-consuming and costly. This emphasis on documentation impedes the application of critical thinking during the validation process, along with opportunities to improve automation via system modernization.

To address these issues, the CDRH, in collaboration with the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) and the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), is planning to release a new guidance document later this year (2021) entitled Computer Software Assurance for Manufacturing and Quality System Software. This guidance will create opportunities for streamlining documentation by shifting the focus of CSV processes towards critical thinking, risk management, patient and product safety, data integrity, and quality assurance.

Even though this guidance is being developed for the medical device industry manufacturing, the FDA has indicated that it will be suitable for R&D, clinical, and other groups within pharmaceutical, biotech and medical device companies that are currently following electronic records and signatures and CSV regulations. The guidance should be considered when deploying non-product, manufacturing, operations, and quality system software systems such as:

- Quality management systems (QMS)

- Enterprise resource planning (ERP)

- Laboratory information management systems (LIMS)

- Learning management systems (LMS)

- Electronic document management systems (eDMS)

With the implementation of this Computer Software Assurance (CSA) guidance, many new opportunities and freedoms will become available to life science companies previously weighed down by the attention to documentation demanded by CSV. In this blog, we will discuss some of the key components of CSA, along with best practices for making the shift.

Computer Software Assurance

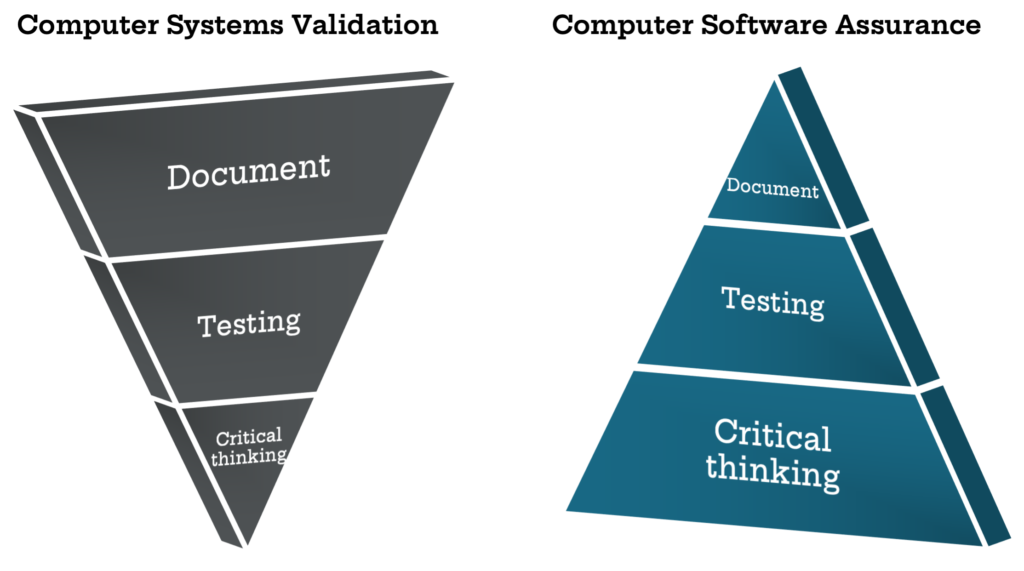

The focus of current CSV processes is producing accurate and approved documentation to present information to auditors. Auditors, such as the FDA, require evidence and records, therefore the CSV methodology inspires a compliance-mindset rather than an innovative one. As such, existing CSV methodology results in manufacturers spending around 80% of their time producing documentation and only 20% of their time doing actual testing of the software.

Documentation will always be a vital part of the process, but it is more important to have a high quality, safe product that meets patient needs, rather than robust documentation that passes an audit cycle. The intention of the upcoming CSA guidance is to support product quality and patient safety by emphasizing critical thinking in the validation process. The FDA wants manufacturers to spend 80% of their time on critical thinking in order to apply the right level of testing to higher-risk activities, with only 20% of time spent documenting.

By stressing critical thinking in the validation process, the FDA is emphasizing a risk-based approach to streamline validation based on the International Society of Pharmaceutical Engineers (ISPE) GAMP® 5 model. This means that while all aspects of the system used in manufacturing must be tested, only components essential to the quality of the product and safety of the patient need to be subjected to full validation rigor. This frees up both testing and validation resources to allow more value-add activities to occur.

The CSA process can be described in four broad steps:

-

- Identify the software’s intended use. The CSA approach starts with identifying intended use of the software or software feature. If the system directly impacts patient safety, device quality, or quality system integrity, then it would be considered a direct system (e.g., software within the device, electronic device history, adverse event reporting, etc.). If it does not, then it would be considered an indirect system (e.g., lifecycle management software).

- Prioritize risk and determine your approach. This is where you use critical thinking to develop a validation methodology appropriate to the risk of the system. The FDA knows that you will have the best insights into how risk is introduced into your products and where it matters, and they expect you to have an element of understanding and control about your product and processes. You’ll want to be able to tell your story to an auditor by explaining in detail where risk is being introduced. For validation purposes, it will be important to delineate where the system in question could introduce risk, versus what is a process risk, and use critical thinking to calculate the risk impact of the system or system feature on patient safety and product quality. Note that a “low risk” designation for a system is only accurate if the system’s failure has no impact on patient safety and product quality. If failure has an impact, then the risk assessment is inaccurate.

- Leverage vendor documentation where possible. Audit your software vendors. If they have quality documentation and validation in place, it can be used for medium and low risk features. You don’t need to perform rigorous validation procedures and extensive documentation for out-of-the-box software that’s already been validated by the software vendor.

- Conduct testing activities based on determined risk level. For high-risk (direct) software and features, extensive validation activities (scripted testing) and documentation will still be necessary. At a minimum, validation activities in this instance will include a test objective for the test script, a step-by-step test procedure, expected results, a pass/fail designation, along with thorough documentation. For medium risk features, vendor documentation or unscripted testing (a test objective and a pass/fail, but no step-by-step test procedure) can often suffice. For indirect systems that do not affect patient safety or product quality, vendor documentation, or in some instances little to no validation at all can be sufficient.

The objective of the CSA guidance is to promote critical thinking, more testing of the system’s intended use, and less functionality testing. As a result, Kalleid expects to see the upcoming CSA guidance lead to less out-of-the box functionality testing and a bigger focus on User Acceptance Testing (UAT), where users test their business processes and the intended use of the system.

Transitioning from CSV to CSA

Too often, process changes like CSA are pasted on top of existing procedures, without taking full advantage of the potential benefits. Though not yet officially released, the CSA concept is already leading to exciting changes in workflow and policy at leading medical device companies. A few key best practices for facilitating the transition from CSV to CSA methodology include:

Perform a validation assessment. To best take advantage of the new CSA guidance, you need to assess your current environment. How much time are you currently spending planning, designing, testing, documenting, etc.? Document your current validation processes, resource utilization, and gaps with CSA methodology.

Develop a transition plan. Now that you have documented your current environment, you can develop a transition plan that focuses on key aspects of the CSA approach – new streamlined validation processes, critical thinking, product quality, patient safety, data integrity, operational efficiency, and effectiveness. This should include quantifiable metrics that allow you to measure your operational performance (e.g., costs, time spent on validation, etc.).

Audit your vendors. Audit your vendors to determine the quality and availability of their validation documentation. This can allow you to begin using vendor documentation to satisfy regulatory requirements for appropriate medium and low risk systems.

Develop a change management plan. You cannot accomplish an effective transition to CSA without supporting your people to make the change. You’ll want to put communication and training programs in place to support changing the culture of your organization from a compliance-centric mindset to quality-focused culture. These programs will support your team in understanding key CSA concepts like critical thinking, risk-based approach, product quality, patient safety, data integrity, value-add activities, etc.

Once the guidance is officially released, the details will become clearer on how best to implement the CSA methodology. Until then, check the CDRH website for the latest updates.

Conclusion

Computer system validation procedures emphasize elaborate documentation requirements to ensure auditors have a detailed overview of all aspects of applications being used to manufacture a product. Instead of assuring product quality, these extensive documentation requirements have become somewhat of a bottleneck and a burden to life science companies, effectively deterring investment in more automated IT solutions.

The new CSA guidelines are the FDA’s attempt to rectify this problem, emphasizing patient safety, product quality, risk control, and critical thinking, which is a major reorientation of the previous CSV framework. Instead of having documentation at the forefront like CSV, the CSA flips this structure completely and establishes critical thinking as its principal phase. Benefits that can be realized from this new approach include reduced software development and implementation times, reduced costs, reduced documentation, and more effective software systems.

As the FDA prepares to release its new CSA guidance, life science companies need to be proactive and develop a strategy to transition to the new CSA methodology that focuses on patient safety, product quality, and data integrity. Industry-leading organizations often partner with knowledgeable consultants to ensure a successful transition from CVS compliance to CSA innovation.